Constraint-based segmentation: A research alternative for systematic exclusion

TL;DR: Random sampling with proper weighting works well when you can reach people proportionally and selection operates similarly across groups.

But systematic exclusion, where entire groups never appear, creates an opportunity for a different approach: define smaller segments by the actual constraints that create exclusion, then achieve representativeness within each segment.

Representativeness is relative to a defined population, not an assumed one. This produces claims that are smaller in scope but more defensible to funders, partners, and decision-makers who need impact numbers they can trust.

When standard sampling meets systematic exclusion

Standard sampling methods work well in many contexts. Random sampling with careful weighting can produce reliable population estimates when you can reach people proportionally, when non-response is manageable, and when selection mechanisms operate similarly across groups. These conditions hold in many research settings.

But systematic exclusion creates a different situation. Sometimes people can't answer because services are blocked, devices don't work, channels are monitored. Others could reach us but won't because the risks are too high or they don't trust the channel.

When entire groups go missing for these reasons, we also lose the information we'd need to construct valid weights—we don't know enough about unreachable populations to calibrate adjustments properly. Standard approaches face fundamental limits. This isn't a criticism of the methods, it's a recognition that the conditions they require don't hold.

Adding more respondents from the same reachable pool gives us tighter confidence in a distorted picture. A larger random sample helps when the problem is random scatter. It does nothing when the people who can answer differ fundamentally from those we need to understand.

Weighting adjustments, selection models, and bounds analysis can address some gaps when we understand the selection mechanism and have strong identifying assumptions.

But when entire groups are systematically unreachable, when we have no valid instrument, no external validation data, and no way to test whether selection operates the same across unobserved groups, then these techniques produce estimates that are precise in the statistical sense but rest on untestable assumptions about the very populations we cannot observe.

The result is conditional precision: tight confidence intervals that are valid only if strong assumptions about unobserved groups hold true.

An alternative: Constraint-based segmentation

Systematic exclusion creates an opportunity: when barriers are explicit and observable, they become the basis for better segmentation. Instead of treating exclusion as a problem to correct through weighting, we treat it as structural information that improves research design.

We start with behavior we can actually see, then build outward carefully. Think of it like drawing a map from landmarks we can physically visit. We mark what we know for certain, sketch the rest in ranges, and make our assumptions visible so others can challenge them.

Step 1: Collect observable anchors

These are verifiable evidence points about awareness, knowledge, attempts, and outcomes. They can come from multiple sources: system traces (connection attempts, error logs, download spikes), survey responses (reported awareness, attempted actions, encountered barriers), partner reports, or help requests. Each observation provides evidence we can point to. When these come from system logs, they establish documented minimums. When they come from surveys, they reveal patterns among those we can reach. In either case, we acknowledge what we cannot observe.

Step 2: Group by constraints, not demographics

Age, income, and location often explain less than the actual barrier someone faces. A person blocked from app stores needs different help than someone under surveillance or someone with an ancient device, even if they share the same demographic profile. When we group by constraint, the path from evidence to intervention becomes obvious.

Step 3: Triangulate across independent sources

We look for the same patterns from different angles. A survey panel suggests a barrier here. Server logs show a matching pattern there. A partner organization confirms the same mechanism through their channel. When different sources converge, we've likely found something real. We can bound our uncertainty around it.

This is where ground truth correction becomes essential. Rather than treating any single source as definitive truth, we use multiple observation methods to calibrate against each other. System logs serve as one reality check; surveys provide another; partner reports offer a third.

When these independent sources point to the same pattern, we gain confidence. When they diverge, that divergence is informative: it may reveal a measurement problem (one source has technical issues), a coverage difference (each source reaches different subpopulations within the constraint group), or temporal change (conditions shifted between measurements).

By systematically investigating disagreements, we learn which measurement approaches work reliably under which specific constraints—making future data collection more effective.

Step 4: Report rough, segment-specific estimates with explicit uncertainty

We don't collapse everything into a single misleading number, but we also don't pretend we can establish precise bounds. For each segment we can observe through surveys:

- State the segment definition clearly (e.g., “people blocked from app stores who responded to our recruitment channels”)

- Report what we observed in that segment (patterns, behaviors, needs)

- Make a rough estimate of segment size with wide uncertainty bounds (”we estimate between X and Y people in this observable segment, though the true number could be substantially different”)

- Explicitly note which related segments we cannot observe and make no claims about them

- Focus on comparative findings across observable segments rather than absolute numbers (”awareness is high in segment A but setup failure is the bottleneck” vs “setup is less problematic in segment B”)

This method works best when observable evidence exists and updates faster than conditions change. It fails when no evidence exists to anchor against, when volatility outpaces validation, when legal or operational requirements demand population-wide extrapolation, or when the most severe constraints leave no observable evidence at all. Even within defined segments, we face selection bias. We study those we can reach within each constraint category, not necessarily a representative sample of everyone facing that constraint.

Tracking drop-off points, not aggregate outcomes

Aggregate measures—”X% of users succeeded”—hide the mechanism. They tell you an average outcome but not which barriers cause failure or where to intervene. When systematic exclusion creates different barriers for different groups, averaging masks what matters.

Observable anchors become especially powerful when we track people through a predictable arc:

- Need appears: a concrete problem demands a solution

- Awareness grows: people learn an option exists

- Attempt happens: they try setup under real conditions

- Success varies: some make it work at least once

- Effectiveness emerges: a smaller group achieves reliable results

A framework like this (need, know, try, succeed, effective) or similar cascades define natural segmentation points. Each stage creates a constraint-defined group we can observe, though we acknowledge that within each stage, we're still studying those who leave traces, not necessarily everyone in that stage. What matters is where people drop off and why among those we can observe, because each drop-off reveals a specific barrier we can address for similar populations.

One segment stalls at awareness because trusted channels never carry the information. Another stalls at setup because the first-run experience breaks under poor connectivity. A third succeeds technically but fails practically because the solution doesn't scale or key partners can't be reached.

An aggregate success rate averages across all three groups and tells you nothing actionable. Separate segment-specific drop-off analysis tells you exactly which barriers hurt which groups, making interventions obvious.

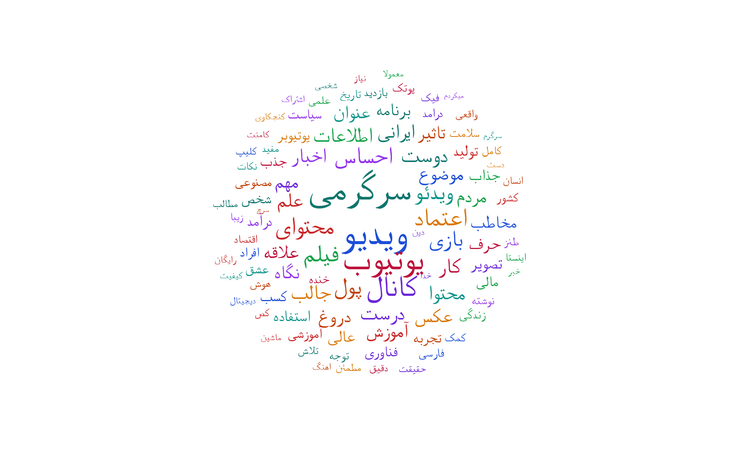

Answering the "how many?" question

What funders and partners actually need

When funders ask “How many people does this reach?” or partners ask “What's the population impact?”, they're asking legitimate questions about scale and importance. We answer these questions differently, in ways that serve decision-making better.

Why smaller segments produce more defensible claims

Traditional research tries to sample from an entire population, discovers it can only reach certain groups, then extrapolates anyway and claims to represent everyone.

The representativeness claim is false because systematic exclusion means the sample doesn't reflect the population structure. Adding more respondents from the reachable pool just tightens confidence intervals around a biased estimate.

Our approach inverts this. We define smaller segments by the actual constraints that create systematic exclusion, then work toward better representativeness within each constraint-defined group.

Within each segment, we still face selection bias (we study those who leave traces, not everyone in the segment), but the bias is more bounded and explicit. We can study “people who attempt to access via circumvention tools and generate observable traces” and separately study “people blocked from app stores who contact support channels.”

Neither is perfectly representative of everyone in that constraint category, but both are more defensible than extrapolating from one biased sample to the entire population. What we gain is explicit boundaries: we know which segment each claim applies to and what selection mechanisms might still bias our view within that segment.

This is the key insight: representativeness is relative to a defined population, not an assumed one. Smaller, more specific segments with explicit selection mechanisms get us closer to defensible claims because:

- We can observe enough of the segment to characterize patterns, even if coverage isn't complete

- The barriers that define the segment are explicit, not hidden in unexplained variance

- The selection mechanisms within each segment are more bounded and nameable

- We don't carry forward compounded bias from one context into claims about another

- Each segment has its own behavioral anchors, so we know which populations generate the data we're measuring

- When we're wrong about a segment, the error is contained, it doesn't cascade into claims about segments facing different constraints

How to present numbers to stakeholders

When someone asks “How many people face this constraint?”, we answer segment by segment with rough estimates and make uncertainty visible, not hidden.

The core principle is encoding certainty level directly into how you present each estimate. Some segments have stronger evidence (larger samples, lower nonresponse, less known bias); others have weaker evidence (smaller samples, channel skew, higher nonresponse).

Make this difference immediately apparent through visual encoding, e.g. edge blur, color saturation, line weight, confidence bands, or any other visual variable that maps naturally to "more certain" vs. "less certain."

For each segment, present:

- Clear segment definition

- Rough size estimate as a range

- Visual encoding of certainty level

- Comparative patterns across segments, not absolute precision

Instead of “We estimate this intervention reaches Y% of the population” (which invites methodological challenges you can't answer), you say: “We surveyed three segments. Segment A shows pattern X with medium certainty; segment B shows pattern Y with lower certainty due to recruitment bias. The actionable difference: segment A needs setup improvements, segment B needs distribution changes.”

When you have a defensible external total (e.g., from authoritative source), you can multiply segment proportions to produce indicative ranges, always labeled as “indicative ranges based on conditional proportions; coverage limits apply.”

What changes is what you can defend. The conversation shifts from “Can we trust these numbers?” to “Given what we observe with varying certainty, which segments should we prioritize?”

This serves institutional needs across contexts

For funding proposals and reports, provide defendable numbers with explicit uncertainty. A standardized disclosure carries most of the weight: explain how you recruited and who that likely missed; name the constraints that define each segment; state the observable anchors and documented minimums they establish; spell out assumptions that expand minimums to probable ranges and plausible maximums; close with the practical claim about what will change for whom and how you'll measure whether it did.

For planning and resource allocation, target resources where evidence is strongest rather than spreading thin based on untestable population assumptions. You can prioritize constraint intensity over raw headcount—showing why a smaller group facing severe barriers often deserves more attention than a larger group with minor friction.

For communicating impact, avoid overclaiming reach while demonstrating rigorous understanding of specific populations. When evidence can't support fine-grained precision, describe patterns and direction honestly. Keep visual language consistent so segments read the same wherever they appear. Above all, make it easy for a reader to see which single assumption would change a number and why, that's how uncertainty becomes a tool for thinking instead of a reason to stall.

How this approach improves research operations

Constraint-based segmentation with observable anchors produces three operational improvements over population-wide estimates under systematic exclusion:

Faster iteration cycles. Because observable anchors can update continuously (server logs, error reports, support tickets stream in daily), we can measure change in days or weeks rather than waiting for annual survey cycles. When we deploy a fix for “people who fail at app store download,” we see impact immediately in download success rates, error reports, and support volume for that segment. This speed advantage is bounded. We can only iterate quickly when conditions change slower than our measurement cadence. In highly volatile environments where barriers shift daily, even continuous monitoring may lag behind change.

Efficient resource allocation. Traditional population estimates under systematic exclusion force you to spread resources across an averaged landscape. You might invest equally in improving awareness and fixing setup problems because both show up in aggregate metrics. Constraint-based segmentation reveals that awareness isn't a problem for your observable groups—they already know about the tool, but setup failure is devastating for the “poor connectivity” segment specifically. You concentrate resources on setup robustness for that segment, not on awareness campaigns that don't address any segment's actual bottleneck.

Defendable claims to stakeholders. When funders or partners ask “How many people does this help?”, population extrapolation under systematic exclusion forces you to make claims you can't defend. A methodologist can challenge your weighting assumptions, your instrument validity, your selection mechanism, and you have no response because those assumptions are indeed untestable. Constraint-based segmentation lets you say “We have high confidence about this group of at least X people who face this specific barrier, with evidence from three independent sources that converge.” Every assumption behind your range is explicit and testable. This moves the conversation from “Can we trust your population estimate?” to “Which segments matter most given our goals?” The second question is productive; the first is not.

Why this matters

We don't need to pretend we can see everyone equally when we can't. This approach isn't a workaround or second-best compromise. It's the most intellectually honest path forward when systematic exclusion exists.

The choice isn't between perfect population representation and messy behavioral research. It's between false precision that misleads decision-makers and honest uncertainty that guides effective action. In constrained contexts, claiming to represent a population you can't actually observe is worse than admitting what you don't know, because it directs resources toward solutions calibrated for imaginary people rather than the real groups you can help.

This work demands three commitments: Start from what we can verify through behavioral traces. Build outward carefully through triangulation and ground truth correction. Stay honest about where knowledge ends and assumptions begin.

When we do this consistently, something shifts. Research stops being an exercise in statistical theater and becomes a tool for understanding how people navigate real barriers and for building solutions that actually reach them. That's not a methodological footnote.

In complex, constrained contexts, it's the difference between research that gathers dust and research that changes outcomes.