What Iranians told us after the blackout

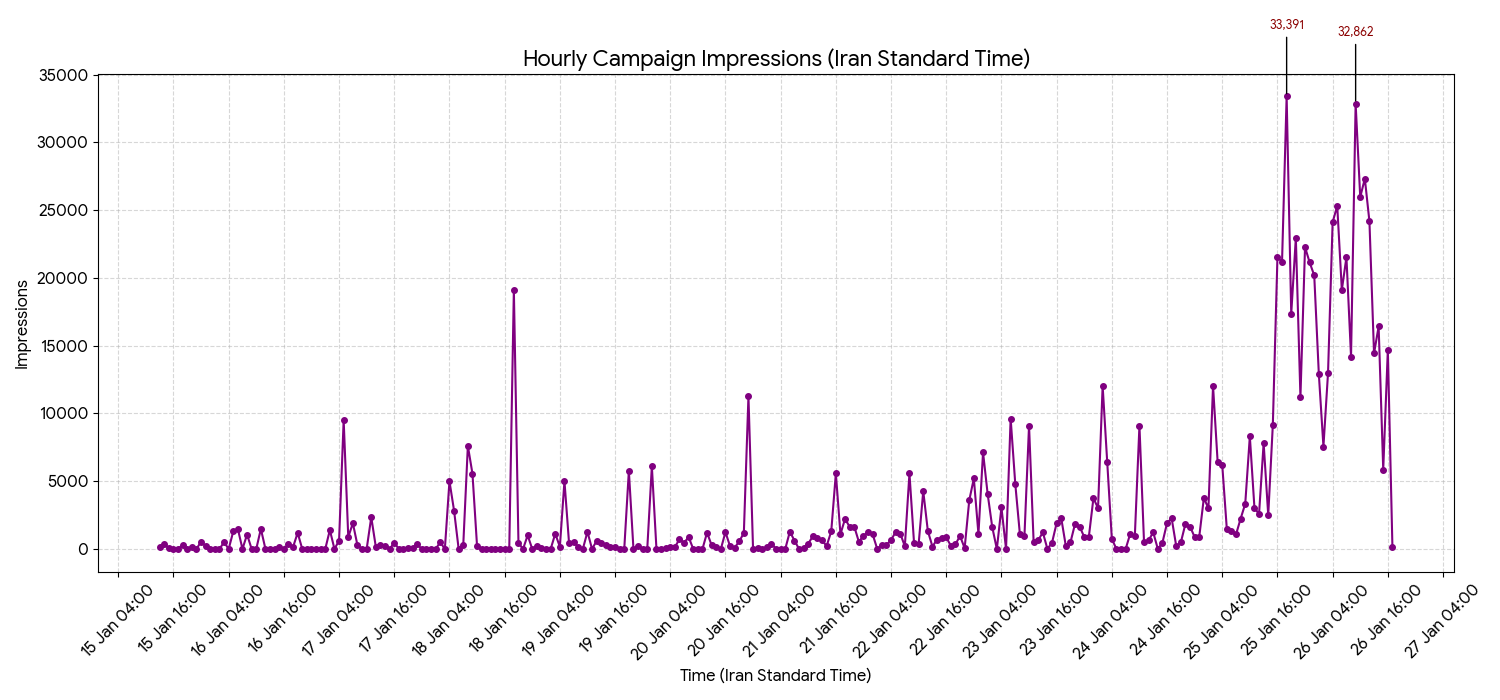

We've been running a small research operation that maintains secure channels into Iran through Telegram and VPN-based ads that are ways for people to tell us what's happening when the news can't get through so we can better understand information needs.

Throughout January, we've been asking a simple question:

What's on your mind?

For most of the past week, those channels went nearly silent. The government had pulled the plug on the internet, and we were left watching from outside like everyone else.

When connectivity started returning on January 22, the messages came flooding back. We received over 220 responses in four days, compared to just 20 in the preceding two weeks.

We had expected to hear about the protests, the crackdowns, the political crisis that outside observers had been tracking through fragmentary reports. Instead, most people wanted to talk about money.

One caveat on the responses we got: This is a convenience sample recruited through Telegram and VPN-embedded links. It is not representative of the Iranian population. Respondents are self-selected, likely more tech-savvy and more connected to circumvention tools than typical Iranians. The data is unweighted. The gender skew toward men may reflect who uses these channels rather than who wanted to respond.

We report these voices to show patterns in what we received, not to generalize about Iranian public opinion.

Here’s what we heard back:

The cost of getting by

Of the substantive responses we received, 32% explicitly mentioned money, poverty, livelihood, or economic conditions. Internet access (the majority of the country are still facing a near-total internet shutdown) came up in 8% of responses.

When you ask people what's on their mind during what looks like a major political crisis, it turns out they're thinking about how to pay for food next week.

A man from Karaj wrote: "Inflation, unemployment, livelihood"

«گرونی بیکاری و معیشت»

"We have no hope for the future."

«ما به آینده هیچ امیدی نداریم»

The responses painted a picture of people focused on getting through the week:

- "Tُhe heavy cost of living" «مخارج سنگین زندگی».

- "Low income, high expenses" «درآمد کم و خرج زیاد».

- "I have no money. I'm unemployed" «پول ندارم.بیکارم».

One respondent framed the entire crisis through this lens:

"The Iranian people are being massacred for a single piece of bread."

«ملت ایران دارن به خاطره یک تکه نان گلوله باران میشوند»

Even when people mentioned protests or politics, the conversation circled back to economics. A man from Tehran said his mind was on "the rising dollar and the protests", «بالا رفتن دلار و اعتراضات», in that order. Several asked us directly for financial help or ways to earn money online.

This pattern is common in autocratic settings. People learn to avoid political talk, even in anonymous surveys, even when politics is the obvious subject. Bread and butter concerns become the safer way to express discontent, and over time they become the genuine focus because when you're struggling to afford food, the question of who governs you feels abstract compared to the question of how you'll eat.

Several asked us directly for financial help or ways to earn money online.

We can't know from these responses how much is self-censorship and how much is simply that economic survival has eclipsed everything else.

The blackout's toll

The internet shutdown has come at huge economic cost, and respondents also shared how it had created its own secondary economic crisis: Several responses revealed how enforced disconnection directly extracted money from people who were already broke.

One man from outside Tehran described paying 150 toman (roughly one USD) for a VPN during the outage while watching a seller process 100 orders for just one person in a single night. The shutdown created a captive market for connectivity.

Another respondent lost cryptocurrency holdings because he couldn't access trading platforms during the blackout:

«دلارهایی usdt رو بخاطر قطع شدن اینترنت در ایران از بین رفت چون یک پلتفرمی قرار بود سود بده ولی کلاهبرداری کرد از من و حسابم را تخلیه کرد در این وضعیت بدی که قرار داریم و من دارم عذاب میکشم»

"I lost my USDT [a stablecoin that mirrors the price of the US dollar issued by Tether dollars] because a platform that was supposed to pay interests/profits scammed me and emptied my account during this bad situation [internet shutdown] and I'm suffering."

A young person from Karaj made the connection explicit:

«اینکه اینترنت سرعتش بره بالا و اینترنت رو حاکمیت قطع نکنه، چون اگه قطع کنه واقعا دیگه حتی برای خوردن نون ساده هم پول ندارم.»

"If the government shuts down the internet again, I can’t even afford to pay for plain bread."

Generational shame

When we asked what people had been discussing recently, responses from the 45+ age group suggested a particular kind of pain: shame in front of their children.

A man from Karaj wrote: "The instability of the country always makes us feel ashamed in front of our children."

«وضعیت نابسامانی مملکت ایرانمان همیشه پیش بچه هامون خجالت زده میشیم»

A woman described her concern as: "Freedom and security and the future of our children. Our own lives are already wasted."

«آزادی وامنیت کشورمون آینده فرزندانمان. خودمان که زندگیمان تباه شدرفت»

Another person mentioned: "The future of our children is the greatest worry of Iranian families."

«آینده فرزندانمان بیشترین نگرانی خانواده های ایرانی است»

The shared concern appears to be a sense of worry about the next generation.

The grind

Beyond the statistics, there was a rawer quality to many responses, a sense of people describing not a political moment but the grinding weight of ordinary existence.

A man from a rural area described his coping strategy: "I'm a simple worker. I work nights, sleep days. My only entertainment is playing on my phone."

«من یه کارگر ساده هستم ... شب سره کار روزم میخوابم سرگرمی من فقط بازی کردن با گوشی»

A woman from Tabriz wrote of a "pointless life in an unsafe world where there is no dignity."

«زندگی بیهوده و دنیای نا امنی که هیچ شرافتی ندیدم»

Another described it as "the most miserable days of our lives since birth."

«مزخرفترین روزهای زندگیمان که از اول عمرمون درگیرش هستیم»

One man's response to "what's on your mind?" was simply “Loneliness”, «تنهایی». His only comfort, he added, was music.

A young woman wrote that her mind was fear of the future «ترس از آینده». Someone else: "My mind isn't working at all. I'm in shock."

«ذهنم اصلا کار نمیکنه در شوکه»

Captive on a broken internet

Even as some people reconnected, the internet remained degraded. One user described the mechanism of control: "My mobile internet is being switched on and off constantly, and upload speeds are heavily controlled."

«نت سیم کارتها به نوبت سویچ ان و اف میشه و بشدت ترفیک اپلود در زمان سویچ ان کنترل میشه.»

another wrote that "we are captive in a prison the size of Iran."

«ما تو زندان بزرگی به وسعت ایران در بندیم»

Others asked when global internet access would return, or requested VPN servers. The functional need to connect ran through the responses alongside the economic and emotional strain.

The weight of it

By the weekend, the dominant tone was not anger but exhaustion, as one man wrote: "Everything is ridiculous."

«همه چیز مسخره س»

"Life is shit."

زندگی» تخمی».

A young person from Isfahan captured something that appeared in several responses, a collapse not into rage but into resignation:

"I want to kill myself. I'm tired of this life and all this hardship."

«من دلم میخواد خودمو بکشم خسته شدم از این زندگی و اینهمه سختی.»

These notes serve to document the emotional state of people emerging from days of enforced silence: exhausted, broke, afraid, and focused less on changing their government than on getting by another week.

The data

Response volume: 240 responses between January 9–25. Of these, approximately 220 arrived after connectivity returned on January 22, compared to just 20 in the preceding two weeks.

What's on your mind? Of substantive responses:

- 32% mentioned money, economy, or livelihood

- 10% mentioned the future, children, or migration

- 8% mentioned internet or connectivity

- 7% mentioned political themes (freedom, government, protests)

Demographics: 89% male, 11% female. Age skewed older: 42% aged 29–44, 34% aged 45+. Education was mixed: 23% had less than a high school education, 39% completed high school, and 39% held a college degree or higher. Largest city concentrations: Tehran (36), Isfahan (15), Karaj (10). 68 respondents listed "other city," and 6 were in rural areas.

We extend our gratitude to the individuals who assisted with data collection and translation for this report. Understandably, they chose to remain anonymous.

In case you missed it: Read our preliminary audit of five major AI models to see how a slight shift in vocabulary in Persian language can flip an answer from human rights documentation to state-aligned propaganda.