How to do manual collection, web scraping, and crowdsourcing data collection

After conducting audience research to identify information needs, create an information map of sources that house data you will need for your reporting.

The information map will show you where your reporting fills gaps in the information environment, and it also sets you up to gather and aggregate data to fill the information needs of that intended audience—this the topic of this post in our series.

Data gathering and analysis is an immense opportunity for newsrooms of any size to fill information gaps for your intended audience. In distorted information environments, its role is all the more important because of lack of free information flows, and it is a huge opportunity for exiled media since it can be more safely filled by remote newsrooms.

While the amount of data available online today is only increasing, that does not mean it is accessible or useful. Identifying a narrow research goal that meets an intended audience’s information needs is the starting point on any data gathering journey toward making sense of the data and rendering it into a relevant and revelatory news product.

Our goal here is to encourage and enable anyone to start a civic scraping project that uncovers hidden or even concealed information that is valuable to any intended audience.

Web scraping is the automated process of systematically extracting large volumes of publicly available information from websites. It can be done by training a tool to seek out data given specific parameters on designated websites or databases.

Civic scraping is the idea of using web scraping as a public interest tool, taking back public ownership and use of data out of the hands of governments or large entities who claim to control it and use legal means to protect it.

Scraping, or automation, is the cornerstone of any data-driven reporting project that requires a large dataset.

Web scraping requires some technical tools and skills but these are not prohibitive and talent is widely available. Even if you don’t have the experience do this yourself, you likely know someone who does, or it can be outsourced.

Instead of focusing on whether you currently have a technical barrier to this process, use your information map to identify what rich data resources exist for your reporting project, and then work to find a way to gather it.

For public health: The National Institute of Health used web scraping of jail records in North Carolina to match inmates with the private database of the health department with the goal of improving health care for incarcerated individuals with HIV, according to a March 2020 research paper that describes the ethical implications of this project.

For volatile housing market trends: Researchers in the UK scraped information related to the housing market to track real-time transactions, leading to insights such as the negotiation margin of buyers. This information was relevant to citizens during the Covid-19 pandemic when the housing market was undergoing rapid changes alongside lockdowns and changes to workplaces and commuting habits.

For climate change research: Data on air quality, carbon emissions, water usage, weather patterns, and more can be scraped and analyzed for insights into environmental changes.

For government accountability: A researcher scraped the Minnesota treasury department’s public records to track government spending and present the data in accessible formats such as charts and graphs.

For social justice: Tax records scraped in the city of Detroit revealed improper property taxes being levied following the 2008 recession, leading to a spate of home foreclosures that disproportionately affected racial minorities.

Once your scraping tool is in place, it will be easier than ever to return to it on a regular basis and continuously gain new insights. This is a great investment. Any scraping effort also grows in insightfulness over time as more data is accumulated.

As you discovered when creating your information map, you are not alone in this process. There are other data gatherers out there in your corner, from researchers to NGOs to impassioned community members like librarians and lawyers. Lean on them in your data gathering process and learn from their techniques and process.

You can also call on the public to crowdsource information with you. Some information, like prices of individual items, may seem so small and time consuming to collect manually, and impossible to collect online. Crowdsourcing asks individuals to go and find that information on a small scale, taking only a few minutes per person. But when aggregated by your team, you can see the broader picture and discover patterns and anomalies.

A February 2024 report by Esri documents how scientists using genomic sequencing to trace illicit pangolin markets needed more samples to trace routes. They called on researchers in Nigeria, Gabon, and Cameroon to go to local markets and ask for a small physical sample.

These 511 samples were tested and reported, resulting in over 100 genome sequences. They identified five distinct groups of pangolins from Sierra Leone to the Democratic Republic of the Congo.

Doing this work themselves, in person and by hand, would have taken an enormous amount and time and resources. It may have also raised suspicions from the sellers in the markets, potentially foiling the research plan.

Unintentional crowdsourcing also happens when many people spontaneously post online with information useful to you, unknowingly contributing to your data gathering efforts. This is just the kind of data that is ripe for civic scraping.

In addition to web scraping, you will of course be doing some manual collection. This might look like downloading reports or spreadsheets found online, a one-time process of collecting, skimming, and logging that data.

We have found that the most effective strategy is a hybrid approach, which combines automated and manual methods to capture the most comprehensive view of your topic. We'll show you how we applied this hybrid method to our project gathering job data in a major city and how you can adapt it to your own work.

The goal of this data gathering process is to create a reliable system for data collection that is resilient in restrictive environments.

Jump: WHY use a hybrid approach | HOW to do manual collection | HOW to do civic scraping | HOW to do crowdsourcing | WHAT we learned

How to set up your hybrid data gathering process safely and securely

For exile media and those working remotely from their intended audience, our relative position of security imposes a certain duty on us to gather and uncover data for the public interest and to do so in a manner that takes into account the safety of those inside the location.

Working in a sensitive environment may require a strong emphasis on security protocols. Always encrypt communications, securely store your data—and delete it when you’re done—and use VPNs or Tor when searching.

In distorted and constrained information environments, no single data gathering method is enough. You will need to choose your own approach for each data source in your information map:

- Relying only on web scraping will miss information that lives in offline channels, private chat groups, or through human sources.

- Relying only on manual collection is slow, resource-intensive, and can’t capture the large, quantifiable datasets needed for trend analysis.

- Crowdsourcing is not appropriate for every data gathering project, but consider its utility for your specific needs.

Overcome technical barriers: Automated data scraping works well for public websites, but content behind logins, in private groups, or in non-digital formats will require manual searching and downloading.

Enhance data quality: Crowdsourcing and manual methods can help you verify the accuracy of automated data and fill in contextual gaps that a machine might miss.

Adapt to a dynamic environment: In a place where platforms and censorship are constantly changing, a flexible hybrid system allows you to pivot and use a different method when one is no longer viable.

In your information map, revisit the column in which you and your team indicated which data gathering method is most useful for that source. Keep in mind technical barriers, data quality, and changes to the information environment.

Manual collection

Manual data collection involves direct human intervention and is the default option we are most accustomed to. Manual collection often means going to a website, searching for data, and capturing it through individual or bulk downloads. This captured information will need to be labeled and stored by your team.

Although it's slower than automated processes, manual collection indispensable for gathering information from places where automated tools are ineffective, such as private chat groups or physical locations.

For sources that offer one-click downloads of data, return limited search results, and or house information in inconvenient formats, manual collection is going to be more efficient than creating a custom tool to download it for you.

However, if the information on the site is constantly updated or changing, consider an automated scraping process using our guide in the next section.

Source cultivation: Cultivate human sources who can provide firsthand testimony, leaked documents, or non-public reports. For example, a reporter might build trust with a member of the intended audience to gain access to information that doesn't exist on public platforms.

Field observation: In less restrictive contexts, manual collection can involve on-site visits to document conditions or gather information that is not available online. However, consider the information available on Google Street View and photos shared on social media of the relevant physical environment, which are accessible online even in restricted environments.

Structuring manual data: To ensure consistency and reliability, we use standardized templates for recording and tagging information. Whether we're collecting interview notes or documenting a physical observation, we record key details like the "who, what, where, when, and how" for each piece of evidence. This helps us maintain a consistent data schema even when the information is unstructured.

Civic scraping

Automating a process for systematically scraping websites or online platforms is essential for efficiently gathering and analyzing large quantities of data.

The first step is to analyze your sources to find good candidates for scraping, since you will be investing resources into the process of setting up and tailoring the scraping automation.

Consider the following factors:

- Entry results limitations: Many websites restrict the number of displayed results to the first 300 - 1,000 entries. To access historical data, you could purchase it directly from the source—which is typically too costly for journalism projects and not possible in many autocratic contexts—or continuously scrape the website.

- Data relevance: Useful information should be accessible directly through the user interface or within metadata by inspecting the website's HTML.

- Search flexibility: You may need to modify your search queries to more easily retrieve relevant data. The simplest method involves identifying an API endpoint and constructing appropriate query URLs.

- Anti-scraping measures: Some websites use CAPTCHAs, IP blocking, and constantly changing HTML structures that inhibit scraping. These defenses don’t have to mean your only option is manual search; we used a combination of request delays and IP address rotation via proxy services to mimic human browsing behavior and avoid being blocked.

An API is an Application Program Interface. It’s what makes a website run in response to your commands.

When you interact with a website, you are making requests of an API, and your request waits in queue before you are served the information you requested.

Undocumented APIs are commands that are visible through your browser’s developer tools, and they give clues about the data, how the website returns search results, and other information not visible when using the site normally.

For more information on undocumented APIs and how to use them for public interest investigations, see inspectelement.org’s guide.

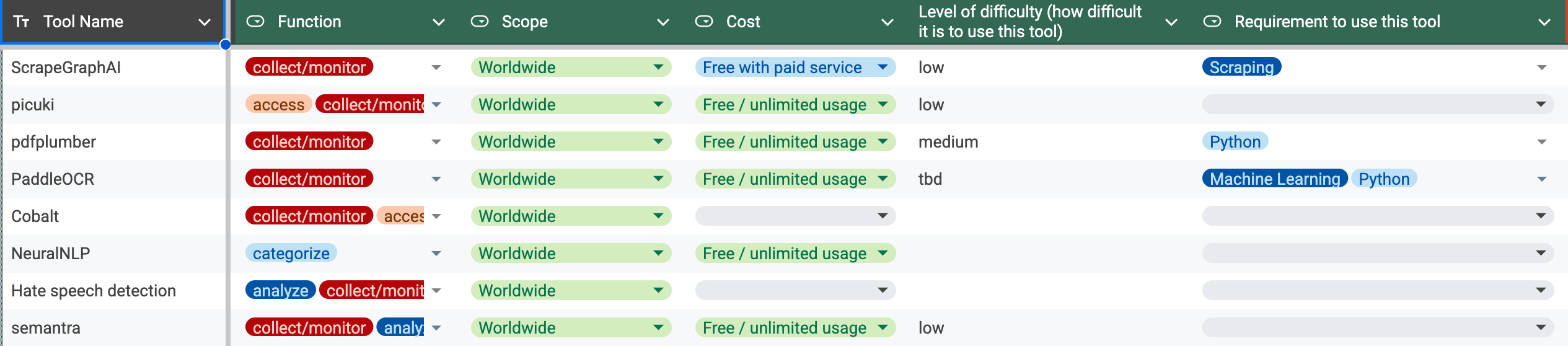

For our research, scraping was necessary for collecting job listings and wage data, which are impractical to gather manually. To do this scraping, we needed some tools, resources, and a developer.

After identifying from our information map the sources we wanted to scrape, we assessed the technical requirements or challenges presented by each source, and what tools we would need to scrape its data.

Then we set parameters for what we wanted to scrape from each site. For example, we didn’t need data that was more than a few months old, and we wanted to focus on just a few key words indicating specific job roles. The purpose of setting strict parameters is to avoid having more data than you need and getting bogged down in cleaning and verifying it later.

Then, our developer designed scripts or programs to carry out the scraping according to our needs.

You don't need a huge budget to get started with this. Many effective tools are open-source and free to use.

Simple scraping: The Python library BeautifulSoup is a simple way to fetch HTML content.

Advanced tools: Use open-source libraries like Playwright and Selenium. These can simulate a full web browser to handle dynamic, JavaScript-heavy websites. This is more robust than simple HTML parsers and is useful for scraping modern websites.

Monitor undocumented APIs: Many sites load data from hidden, or undocumented, APIs. We used our browser's developer tools to monitor network traffic and discover these API endpoints, which allowed for a more reliable and efficient data extraction than scraping the HTML directly.

Cloud hosting: Providers like DigitalOcean offer affordable cloud servers that are perfect for running scraping scripts on a schedule. For large datasets, we ran our scraping scripts on DigitalOcean rather than on a local machine to ensure continuous data collection without manual intervention. We automated the process using GitHub Actions to run the scripts on a regular schedule, which helped us manage workloads.

Our developer worked to create an automated system to scrape the data we requested into a spreadsheet, and they ran this tool on a weekly basis for us. Our researchers had access to the spreadsheet for cleaning and analysis.

Remember that it’s possible to adjust the parameters for the data scraping if you notice that the search is too broad or irrelevant items are frequently popping up. The goal of an automated system is to save you time, in addition to accessing data that’s not feasible to acquire manually, so make sure the system is working for you.

Crowdsourcing

Crowdsourcing leverages the collective power of your audience to gather and verify information at scale. This method is especially valuable for real-time reporting, for verifying incidents, and for gathering dispersed, anecdotal information that no single reporter could collect alone.

Crowdsourcing combines an element of manual search with the power of aggregating that data through the internet.

The term itself was coined by Jeff Howe in Wired magazine in 2006. Crowdsourcing had its major moment in journalism in an era of rising use of social media platforms and hashtagging, and before newsrooms began to shrink and cut such projects.

Some notable examples from that era:

The Guardian's MP expenses scandal: In 2009, The Guardian crowdsourced the review of 458,832 expense documents from UK members of parliament. Over 20,000 people helped review nearly half the documents in just 80 hours, uncovering numerous scandals.

ProPublica's "Free the Files": In 2012, ProPublica recruited volunteers to track political ad spending by examining thousands of TV station documents, creating a comprehensive database that would have been impossible for journalists to compile alone.

In our project on wage information for blue-collar workers, research shows that many workers rely on informal networks for job information.

Although we did not use crowdsourcing in our project, such a strategy might have allowed us to tap into these networks directly and request wage, benefits, and cost of living data from those in the job role we identified.

This system could allow for anonymous submissions, providing a rich, on-the-ground view that complements our scraped data and helps us verify what we find on official platforms.

What we learned

The possibilities for civic scraping are basically limitless, but it is essential to have a narrowly-defined research topic or question before you begin, to avoid an overload of data.

However, one of the purposes of scraping the data is to find out what insights can be gleaned, so there is a balance between too narrow and too broad of a focus.

For example, in our project, we scraped a relatively narrow set of data related manual labor jobs. We observed some broad findings that revealed a number of insights for our audience:

- Geographic job disparity: Job opportunities are heavily concentrated in the relevant cities’ urban cores, creating challenges for workers in outer districts.

- Benefits over salary: Jobs offering benefits like accommodation and meals can provide greater financial stability and savings potential, despite having a lower base salary.

- Experience is key: For blue-collar workers, experience is a much stronger predictor of wage growth than formal education.

After analyzing these jobs as a whole, we found that one specific job role was ideal for moving forward with our reporting. If we hadn’t scraped a wider data set, we may have arbitrarily chosen a different job role to focus on, or missed the patterns described above. But if we had scraped too many job categories, it may have been too unwieldy or time consuming to work with that data.

Our early insights were made possible by systematically gathering and cleaning our data. Next, we will explain how we standardized our messy data, categorized it, and performed trend analysis to uncover these and other important stories.

Join us on our process in the Audience Research, Reporting, and other phases. If you haven’t already, sign up to our newsletter so you don’t miss out.

If you have feedback or questions, get in touch at hello@gazzetta.xyz.